In May 2020, AIS caused a colossal mishap when it accidentally leaked 8.3 billion records of customers’ internet usage data.

The leaked data exposed 3.3 billion DNS query logs and five billion NetFlow logs from 11 million unique IP addresses over eight days to the public.

What do these data reveal about the users?

The trove of our data lies in our web usage

Our Internet Protocol address (IP address) is like our home address or phone number. Electronic devices that can connect to the internet are identified by an IP address given out by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) such as AIS, True, 3BB, etc.

Our smartphone. The router we use to connect to WiFi at home. They can all be used to trace back to us by ISPs.

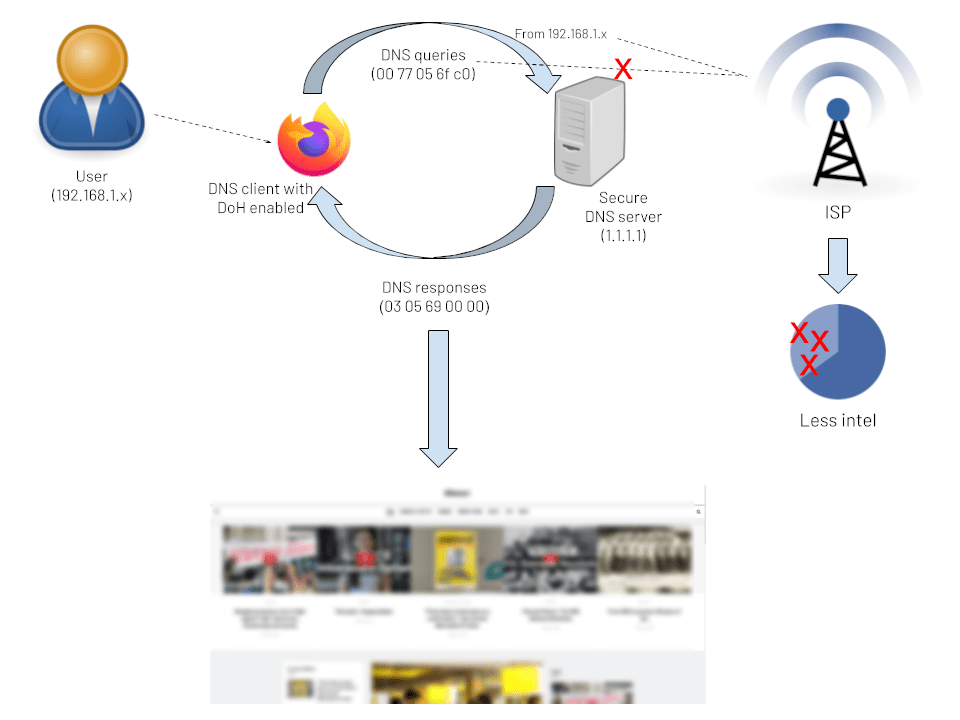

When we enter a website or open an app, the browser/app sends a request to the destination website so we can access it. This is called a Domain Name System (DNS) query. A DNS query is sent from a DNS client (our web browser) to a DNS server.

A DNS server is like the Contacts app on our phone that keeps all the website names (domain name) that people can understand and link them to the underlying IP addresses that machines can understand. As a result, IP addresses can be changed without breaking the link to the domain name.

When a DNS query is sent, our device’s IP address is also attached to the request. ISPs also keep detailed internet usage traffic of its users (NetFlow data in AIS’s case). This allows ISPs to correlate DNS queries associated with our IP address with the web traffic data and map out the websites we visited and roughly how much time we spent on each site.

Over time, this can be used by ISPs (or anyone who can intercept web traffic, e.g. hackers, spy agencies) to gain an understanding of our online behavior.

It’s called ISP snooping.

What can ISPs do with our web browsing data?

Even though the leaked data cannot be used to identify users’ identities, it gives an insight into how ISPs have the potential to pry into our web browsing history and see every detail of our online personal life if they so choose.

Since PDPA is not yet enforced, they can choose to sell our data to third-party companies that may use our web history for marketing purposes without our consent. Generally, those companies won’t know the specific details of our online identity because the ISPs often anonymized our data first. It’s still creepy, nonetheless.

The scarier bit is, sometimes, our ISPs cannot choose. If the government wants to know the web history of “a person of interest” and manage to ask the court to issue an order for that information to be disclosed, the ISPs have no choice but to hand over the data, without any anonymization.

“Niranam” comes to mind.

When he was arrested, the police said they asked for the IP addresses that accessed Niranam’s Twitter account from True Move H.

The mobile carrier promptly complied, and the IP addresses were traced back to Niranam’s phone number, eventually leading to his arrest.

So clearly, the possession of such information by ISPs creates risks for users. From letting other companies know too much about the users to the restriction of their freedom of expression.

What can protect us from ISP snooping?

There are many ways to protect ourselves from ISPs snooping around our web browsing history.

But the cheapest (i.e., free) and the easiest option is to encrypt our DNS queries.

Encrypting DNS queries prevents ISPs from reading them by exchanging an encryption key with a secure DNS server first so only the server can understand your request. The query is then encoded by our browser/app to ensure that the ISP cannot understand it. Finally, the encrypted DNS query is sent on its way to the DNS server.

When the query reaches the DNS server, the server will use the key to decode the message and send the IP addresses of the destination website back to the user in the same manner.

The most popular method of DNS encryption is DNS Queries over HTTPS (DoH), which uses the HTTPS protocol already supported by virtually all web browsers and customarily used to securely transfer data between the user (via a web browser/an app) and the destination website.

Encrypting DNS queries does not entirely secure us against snooping. For example, AIS can still learn their users’ online behavior using NetFlow data. But it does make snooping a lot more complicated, because it forces the snoopers to translate the IP addresses into domain names themselves, instead of relying on DNS servers.

To completely secure our internet browsing, we should pair DNS query encryption with Virtual Private Networks (VPN) service, a good one usually costs money, or use Tor, which is less user-friendly and has its limitations.

How can we encrypt DNS queries?

PC and Mac users have many ways to enable DoH based on our computer expertise. Still, the easiest way is to use Firefox web browser and allow its DNS encryption functionality. In Firefox, go to Options > Network Settings > check “Enable DNS over HTTPS” and click OK.

iPhone and Android users can download 1.1.1.1 in App Store and Play Store, respectively. The app, once installed and activated, routes all DNS queries to a secure DNS server hosted by Cloudflare, an internet security company.

This article was originally published at https://thisrupt.co/lifestyle/ip-address-snooping/ on June 29, 2020 and authored by Kanop Soponvijit, the owner of this blog.